For my eternal disappointment, it isn't Godzilla or Nessie. But check out this video by the DIY channel and find out what is it! ~Ally

0 Comments

Imagine you're woken up in the middle of the night by a frightening sound. You haven't been sleeping for days, since the ground of the camp isn't a very comfortable bed. Rain and strong winds are also common in these camps and the lack of food is always present. But the worse is the thought of the upcoming dawn: the batlle day approaches, and you don't want to die, but have to fulfill your Christian duty to fight against you enemies. Many of your friends will perish in this day, and you'll probably see many other people die horribly. But you must stay. And try not to get killed. That's what medieval knights faced everyday in the great (and small) battles and wars we hear and read about nowadays. In movies, medieval knights are usually portrayed as courageous and loyal heroes who will fight to the death without fear or regret. But, according to a new research by Thomas Heeboll-Holm, a medieval historian at the University of Copenhagen, this wasn't the case. In reality, he claims, the lives of knights were filled with a litany of stresses much like those that modern soldiers deal with. Which could indlude Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other related illnesses. People who are diagnosed with the disorder, often suffer from uncontrollable and intense stress for at least a month after a horrifying event. Symptoms can include flashbacks, nightmares, depression and hyperactivity. When soldiers go to war in modern times, Heeboll-Holm said, psychologists now recognize that the stresses they encounter can lower their psychological resistance until they finally succumb to anxiety disorders. Since medieval knights faced as many and possibly more hardships than modern soldiers do, he wondered if he might be able to find references to signs of trauma in warriors who fought during the Middle Ages. To get an idea of how things worked in that time, we can look at this excerpt by the 14th-century French knight named Geoffroi de Charny: "In this profession one has to endure heat, hunger and hard work, to sleep little and often to keep watch. And to be exhausted and to sleep uncomfortably on the ground only to be abruptly awakened. And you will be powerless to change the situation. You will often be afraid when you see your enemies coming towards you with lowered lances to run you through and with drawn swords to cut you down. Bolts and arrows come at you and you do not know how best to protect yourself. You see people killing each other, fleeing, dying and being taken prisoner and you see the bodies of your dead friends lying before you. But your horse is not dead, and by its vigorous speed you can escape in dishonour. But if you stay, you will win eternal honour. Is he not a great martyr, who puts himself to such work?" Charny showed no signs of instability, Heeboll-Holm said, but he repeatedly expressed concern about the mental health of other knights. And there is no doubt that medieval knights suffered a lot, according to other historians. Tales from that era include all sorts of gruesome details. Many tell of warriors vomiting blood or holding their entrails in with their hands. One mentions a Castilian knight who gets a crossbolt stuck up his nose in his first fight. Another tells of a fighter getting slashed by a sword through his mouth. Again and again, there are references to bad food, uncomfortable conditions and relentless fighting. After so many centuries, though, it can be challenging to interpret old texts. Part of the problem is that knights never psychoanalyzed themselves, at least not in print. Instead, they either offered advice to other knights about how to act in various situations or they simply recounted events. One of the biggest differences between now and then, researchers add, is that medieval knights were usually born into their elite and noble order, and they were trained from a young age to think of themselves as warriors who fought in the name of Christianity. Modern soldiers, on the other hand, often leave a very comfortable life for one of violence and trauma. ~Ally

I've been dealing with the Engligh language - and, particularly, the American way of speaking -, for quite some time now, as a translator and teacher, but, these days, I came accross some words that have different meanings according to the country you're in. So here are some examples: Cheers

Alright

Cheeky

Tutor

Jumper

~Ally

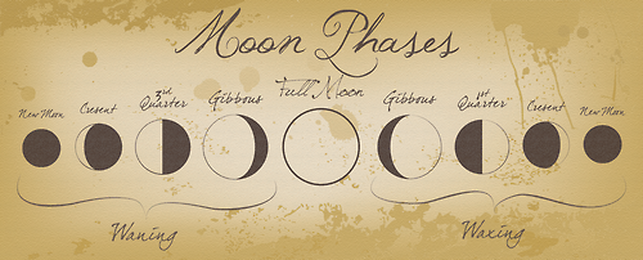

As you might easily guess, a lunar calendar is based on cycles of the lunar phases. Because there are slightly more than twelve lunations or synodic months (months with approximately 29 days) in a solar year, the period of 12 lunar months (354.37 days) is sometimes referred to as a lunar year. A common purely lunar calendar, for example, is the Islamic calendar or Hijri Qamari calendar. A feature of the Islamic calendar is that a year is always 12 months, so the months are not linked with the seasons and drift each solar year by 11 to 12 days. It comes back to the position it had in relation to the solar year approximately every 33 Islamic years. It is used mainly for religious purposes, but in Saudi Arabia it is the official calendar. Other lunar calendars often include extra months added occasionally to synchronize it with the solar calendar. The oldest known lunar calendar was found in Scotland; it dates back to around 10000 BP. Curiously, though, most calendars referred to as "lunar" calendars are in fact lunisolar calendars. That is, months reflect the lunar cycle, but then intercalary months are added to bring the calendar year into synchronisation with the solar year. Some examples are the Chinese and Hindu calendars. Some other calendar systems used in antiquity were also lunisolar. All these calendars have a variable number of months in a year. The reason for this is that a solar year is not equal in length to an exact number of lunations, so without the addition of intercalary months the seasons would drift each year. To synchronise the year, a thirteen-month year is needed every two or three years. Some lunar calendars are calibrated by annual natural events which are affected by lunar cycles as well as the solar cycle. An example of this is the lunar calendar of the Banks Islands, which includes three months in which the edible palolo worm mass on the beaches. These events occur at the last quarter of the lunar month, as the reproductive cycle of the palolos is synchronised with the moon. Even though the Gregorian calendar is in common and legal use, lunar and lunisolar calendars serve to determine traditional holidays in many parts of the world, including India, China, Korea, Japan, Vietnam and Nepal. Such holidays include Ramadan, Diwali, Chinese New Year, Tết (Vietnamese New Year), Mid-Autumn Festival/Chuseok and Nepal Sambat and Mongolian New Year as called Tsagaan sar, to name a few. ~Ally

Today's post is another TEDx talk, but this time with some tips for us polyglot-wannabes. If they work or not? Well, that's something each one of us will have to see for themselves. ~Ally

Remember what I told you about the Gregorian Calendar yesterday? Well, I purposely forgot to mention that the alterations were made in the Julian Calendar, which was stablished as a reform of the Roman Calendar by none other than Julius Caesar in 46 BC. It was the predominant calendar in most of Europe, and in European settlements in the Americas and elsewhere, until it was refined and superseded by the Gregorian calendar. The difference in the length of the year between Julian (365.25 days) and Gregorian (365.2425 days) is 0.002%, that is - if you're not so good at math like me -, 13 days. In short: the Julian Calendar is 13 days behind the Gregorian Calendar. Savvy? Let's explain it a little bit more: the Julian calendar has a regular year of 365 days divided into 12 months, as listed in Table of months. A leap day is added to February every four years. The Julian year is, therefore, on average 365.25 days long. It was intended to approximate the tropical (solar) year. Although Greek astronomers had known, at least since Hipparchus, a century before the Julian reform, that the tropical year was a few minutes shorter than 365.25 days, the calendar did not compensate for this difference. As a result, the calendar year gained about three days every four centuries compared to observed equinox times and the seasons. This discrepancy was corrected by the Gregorian reform of 1582. The Gregorian calendar has the same months and month lengths as the Julian calendar, but inserts leap days according to a different rule. The Julian calendar has been replaced as the civil calendar by the Gregorian calendar in almost all countries which formerly used it, although it continued to be the civil calendar of some countries into the 20th century. Most Christian denominations in the West and areas evangelized by Western churches have also replaced the Julian calendar with the Gregorian as the basis for their liturgical calendars. However, most branches of the Eastern Orthodox Church still use the Julian calendar for calculating the dates of moveable feasts, including Easter (Pascha). Some Orthodox churches have adopted the Revised Julian calendar for the observance of fixed feasts, while other Orthodox churches retain the Julian calendar for all purposes. Believe it or not, the Julian calendar is still used by the Berber people of North Africa and on Mount Athos. ~Ally

For some unknown reason, I always believed that the Gregorian calendar was something I'd never seen in my life. So you can imagine how surprised I was to find out that this is not only the civil calendar, but also has been the unofficial global standard for decades and is recognized by several international institutions. It is also called the Western calendar and the Christian calendar and it was a refinement made in 1582 to the Julian calendar amounting to a 0.002% correction in the length of the year. The motivation for the reform was to bring the date for the celebration of Easter to the time of the year in which the First Council of Nicaea had agreed upon in 325. Because the celebration of Easter was tied to the spring equinox, the Roman Catholic Church considered this steady drift in the date of Easter undesirable. The reform was adopted initially by the Catholic countries of Europe. Protestants and Eastern Orthodox countries continued to use the traditional Julian calendar and adopted the Gregorian reform after a time, for the sake of convenience in international trade. The last European country to adopt the reform was Greece, in 1923. The Gregorian reform contained two parts: a reform of the Julian calendar as used prior to Pope Gregory XIII's time and a reform of the lunar cycle used by the Church, with the Julian calendar, to calculate the date of Easter. The reform was a modification of a proposal made by Aloysius Lilius. His proposal included reducing the number of leap years in four centuries from 100 to 97, by making 3 out of 4 centurial years common instead of leap years. Lilius also produced an original and practical scheme for adjusting the epacts of the moon when calculating the annual date of Easter, solving a long-standing obstacle to calendar reform. In addition to the change in the mean length of the calendar year from 365.25 days (365 days 6 hours) to 365.2425 days (365 days 5 hours 49 minutes 12 seconds), a reduction of 10 minutes 48 seconds per year, the Gregorian calendar reform also dealt with the accumulated difference between these lengths. Between AD 325 (when the First Council of Nicaea was held, and the vernal equinox occurred approximately 21 March), and the time of Pope Gregory's bull in 1582, the vernal equinox had moved backward in the calendar, so that in 1582 it occurred about 11 March, 10 days earlier than 21 March. The Gregorian calendar therefore began by skipping 10 calendar days, to restore 21 March as the date of the vernal equinox. Though not part of the Gregorian calendar itself, the reformed calendar continued the previous year-numbering system (Anno Domini), which counts years from the traditional date of the Nativity, originally calculated in the 6th century and in use in much of Europe by the High Middle Ages. This year-numbering system, now also called the Common Era, is the predominant international standard today. ~Ally

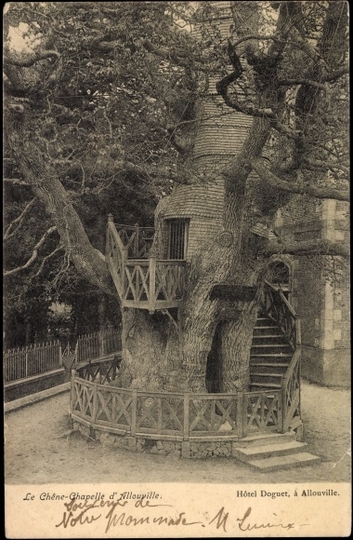

Although I've never been quite a church-going person, I do enjoy cathedrals and churches, especially when it comes to their unique and sometimes remarkable architecture. If I had to pic a favorite, it would be very hard, but the oak Chapel of the small French village of Allouville-Bellefosse is definetely on my top 3.

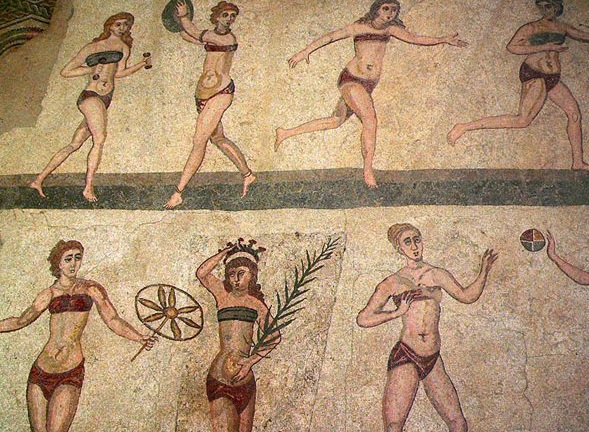

It is literally built on an ancient oak tree, where a staircase spirals around its twisted trunk, which makes me remember a tree house. Within there are two small chapels, which are to this day used as places of worship by the local people. How old the tree is exactly is still the subject of some debate but it is without doubt the oldest known tree in France. While Chêne Chapelle (Oak Chapel) has persevered through the centuries, others have come and gone. So you can get an idea of how old it is, it was growing when France became a truly centralized kingdom under Louis IX in the thirteenth century. It survived the ravages of the Hundred Years War with the English. The Black Death, the Reformation, the Revolution and the time of Napoleon all came and went as it spread its branches. Local folklore places the time at which the acorn first took root as a thousand years ago. They maintain that William the Conqueror said prayers at its base before he went off to thrash the Anglo-Saxons near a small seaside town called Hastings. Yet tree experts put the real age of the tree at around 800, which puts its roots firmly in the thirteenth century. But, as many things in life, the Chapel has also suffered some damages. A catastrophe occurred in the late 1600s, when the oak was nearing 500 years in age. On one stormy night it was struck by lightning, and a bolt with a temperature approaching 30,000 °C pierced the magnificent tree to its heart. Yet instead of dying, something astonishing happened. The fire within burned slowly through the center and hollowed the tree out. Perhaps it should then have simply slowly rotted away, but each year new leaves would form and the tree would produce acorns in abundance. In those religious times it was not long before the miraculous tree gained some pious attention. The local Abbot Du Detroit and the village priest, Father Du Cerceau, determined that the lighting striking and hollowing the tree was an event that had happened with holy purpose. So they built a place of pilgrimage devoted to the Virgin Mary in the hollow. In later years, the chapel above was added, as was the staircase. The need to survive sometimes precipitates change. During the Revolution the tree became an emblem of the old system of governance and tyranny as well as the church that aided and abetted it. A crowd descended upon the village, intent on burning the tree to the ground. However, a local whose name is lost to history had an inspired thought: he renamed the oak the temple of reason and as such it became a symbol of the new ways of thinking and the chapel was spared. Of course, a tree this old cannot go on forever and Chêne chapelle is showing its age. Poles must shore up its weight where it once it bore its own, like a giant stretching. Wooden shingles have been used to cover areas of the tree which have lost their bark. Yet as much care and diligence is given to the tree as can be, to ensure that it lives on as long as possible even though part of its trunk is already dead. Yet twice a year its loyal congregation gathers and mass is celebrated within the confines of this remarkable chapel of oak. The chapels are called Notre Dame de la Paix (Our Lady of Peace) and the Chambre de l'Ermite (Hermit's Room). On August 15 of each year it is still a site of pilgrimage for local Christians. I'm not sure why I thought they didn't in the first place, but whatever. They did. Under those famous Roman togas, both men and women wore a loincloth called a subligaculum, made from wool or linen, although silken undergarments were prized by the wealthy. Women also sometimes wore a kind of strapless proto-brassiere called a mamillare or strophium. It was common for younger women especially to bound their breasts tightly, sometimes with soft leather. ~Ally

I know it's only tomorrow, but Google and I couldn't wait! Up until today I believed that Woman's Day began as a memorial of a group of women who died in a factory fire accident back in the 1900's - don't ask me why, I can't quite remember! Although I've read that many people also make that mistake -, but it's actual origin comes from the manifestations of Russian women for better life and work conditions and against the entry of tsarist Russia in the First World War. These manifestations also marked the beginning of the 1917 Russian Revolution. With the advent of Stalinism, the International Woman's Day became an element of the party propaganda. However, the idea of celebrating a woman's day had already appeared since the first couple years of the twentieth century in the USA and Europe, in the context of women fighting for better life and work conditions, as well as for the voting right. In the West, though, the International Woman'sDay was celebrated from the beginning of the century until the 1920's, when it fell in disuse. The date was forgotten for a long time and was only recovered by the feminist movement in the 1960's. In 1975 the UN stablished 1975 as the International Woman's Year and march 8 was chosen to celebrate women and their social, political and economical achievements in 1977. Sadly, nowadays, it has completely lost its original sense, acquiring a festive and shallow commercial nature. ~Ally

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed